Europe

Kraków

We were up early this morning to get organised to spend the day in Kraków, the former royal capital of Poland. Unlike Warsaw, which was decimated in WWII, Kraków’s historic areas survived relatively unscathed, and we were looking forward to exploring the city.

We caught a taxi from the hotel just after 7:00 am, to make sure we arrived at the Warsaw Central train station in plenty of time for our 7:40 am departure.

We had a private cabin for the two-and-a-half-hour trip, which was nice.

After a very comfortable journey, we arrived in Kraków just after 10:00 am. We found the taxi rank, and hopped in a taxi to head to Wieliczka, to visit the salt mine. The Wieliczka Salt Mine is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the world’s oldest operational salt mines, dating back to the 13th century. The tunnels of the mine stretch over 287 kilometers across nine levels, but only about 2% of them are accessible to visitors. The mine contains more than 2,000 chambers, reaching depths of over 327 meters (which is equivalent to the height of a 109-story skyscraper) beneath the surface.

As we walked into the mine area (set in a surprisingly beautiful garden area), we passed one of the more modern tunnelling machines that have been used in the mine. Mechanised tunnelling methods were only introduced in earnest in the 20th century, so the vast majority (well over 80%) of the tunnelling in the mine has been done by hand.

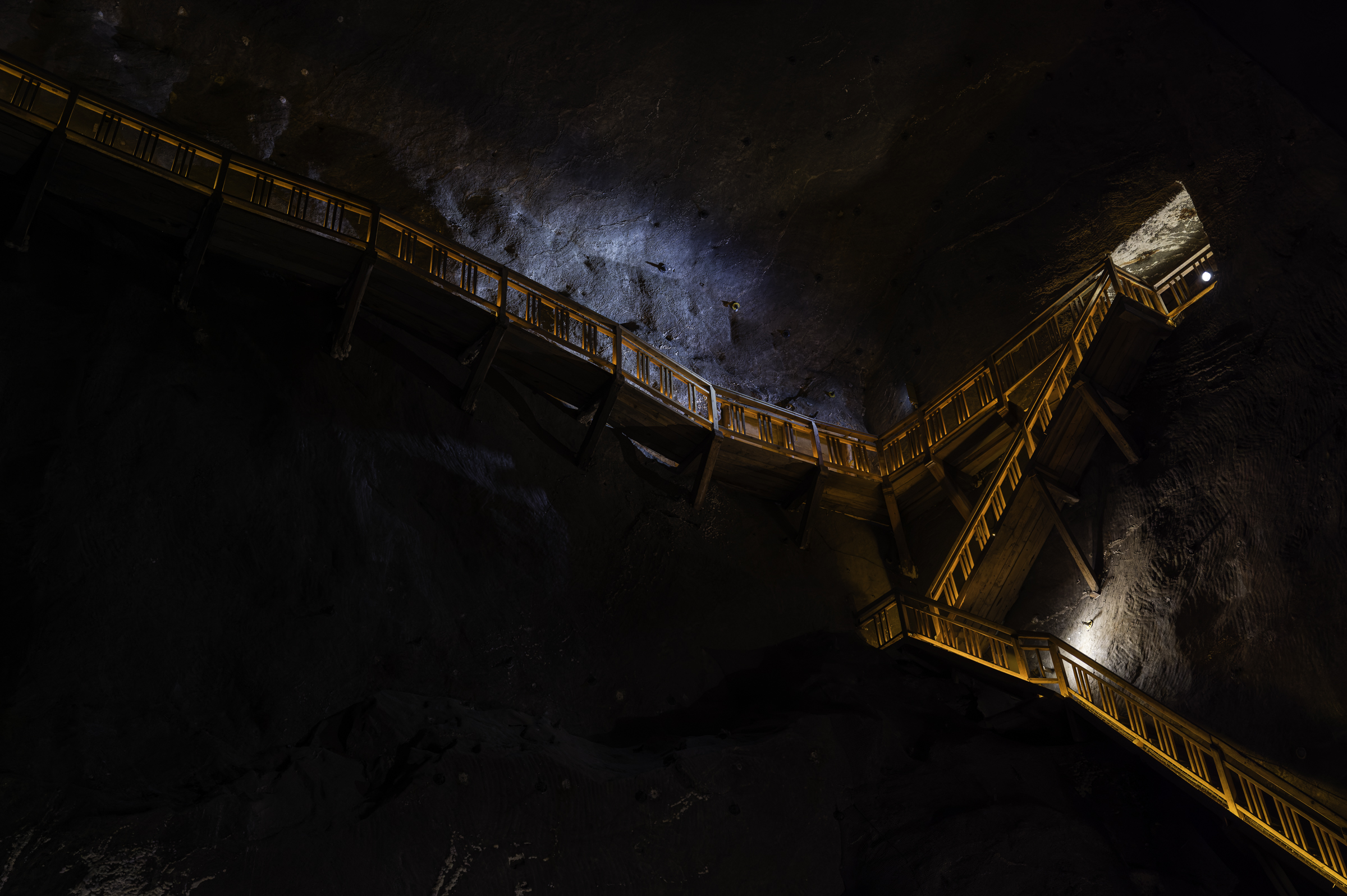

We met our guide at the mine entrance at ground level, before descending 40 flights of stairs to start the tour proper. We spent about two hours underground, and we found the mine quite fascinating.

The mine contains an incredible collection of sculptures, many of which were carved by miners who were self-taught sculptors. More recently, some sculptures have been created by notable, contemporary Polish artists.

One of the more high-profile sculptures is the story of Princess Kinga’s ring. This sculpture shows Princess Kinga (later Saint Kinga of Poland) receiving a salt crystal from a miner. According to legend, Kinga threw her engagement ring into a salt mine in Hungary; miraculously, miners in Poland later discovered the ring inside a block of salt in Wieliczka, symbolising her gift of salt wealth to Poland.

The most impressive chamber we saw was St. Kinga’s Chapel. This chapel is the world’s largest underground church and, like almost everything in the mine, is carved entirely out of salt. Even the chandeliers are carved from salt! Its main altar houses relics of St. Kinga, the patron saint of salt miners.

As we left the chapel, our guide pointed out, what looked like, individual floor tiles. However, the floors in the mine are not individually tiled; rather, the floors are solid rock salt, with carvings done to mimic individual tiles. Quite incredible.

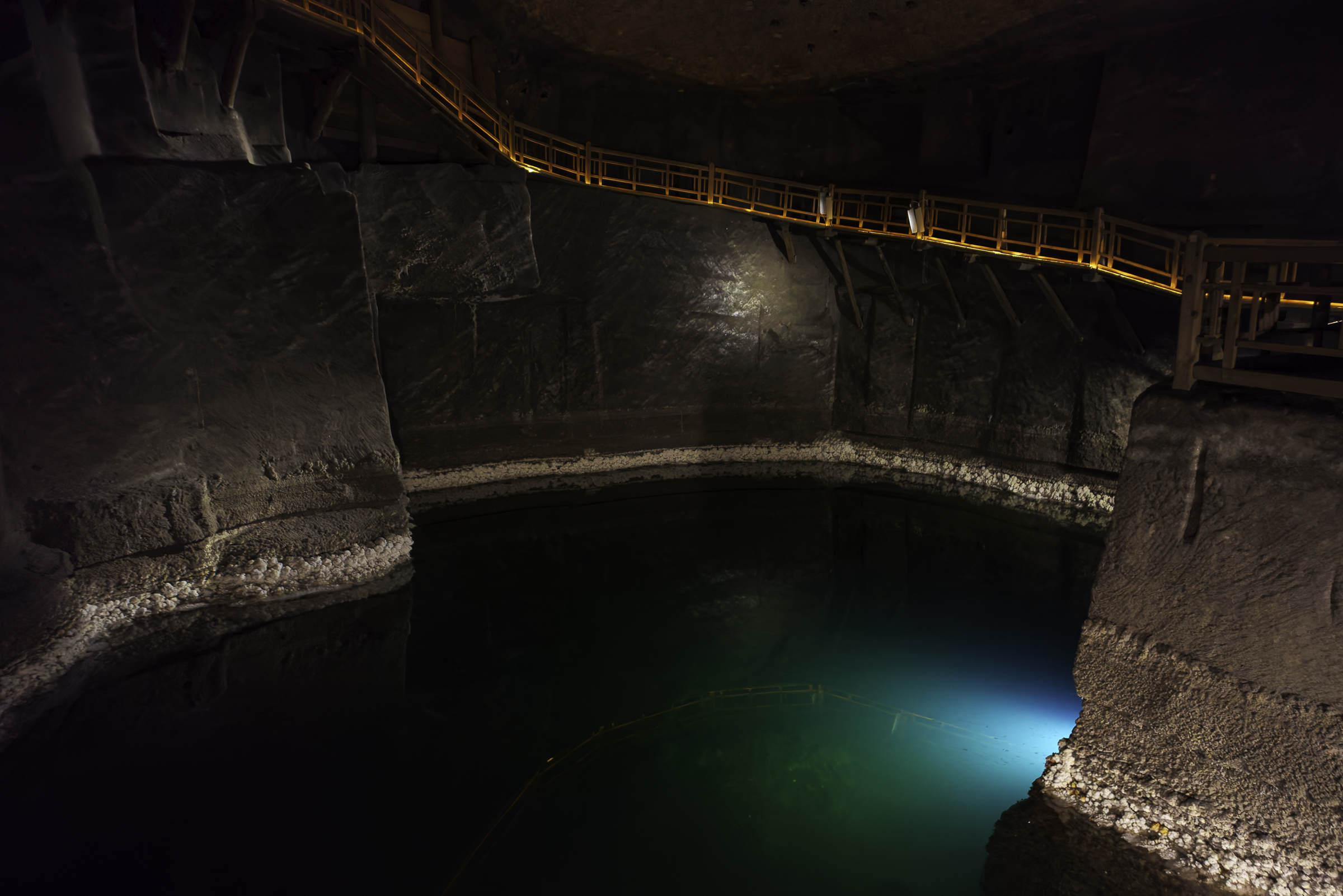

Along the way, we passed a number of very pretty underground lakes.

After having descended by foot to around 140 metres below ground level, we were relieved to find out that we would be going back to the surface via an elevator. However, as we arrived at the elevator, we were advised that it had just stopped working, so we embarked on a very long walk to the next working elevator.

We left the salt min around 1:00 pm, and caught a taxi back into Kraków. We negotiated with one of the local tourist operators to take us in his vehicle (a sort of oversized golf cart) on a tour of the city. We started out by heading to Kazimierz, the historic Jewish Quarter of town. Our first stop was Plac Bohaterów Getta (Ghetto Heroes Square). The large metal chairs in the square are part of a memorial called “The Empty Chairs”, made up of 70 empty chairs, commemorating the victims of the Kraków Ghetto during the Holocaust. It is a deeply moving space.

On a corner of Ghetto Heroes Square is Apteka pod Orłem (Pharmacy Under the Eagle). This pharmacy was run by Tadeusz Pankiewicz, one of the few non-Jews allowed to remain within the ghetto’s boundaries during WWII. The pharmacy became a safe haven, a distribution point for medicine and supplies, and a gathering place for people seeking help and information during Nazi occupation. Pankiewicz and his staff courageously aided residents by providing shelter and medical care, as well as falsifying documents, all at great personal risk. Today, the pharmacy is a museum that honours his heroism.

Not far from the Pharmacy Under the Eagle is the factory is the enamelware factory that was owned by Oskar Schindler, about whom Thomas Keneally wrote the book “Schindler’s Ark” (on which the movie “Schindler’s List” was based). Oskar Schindler was a member of the Nazi Party who profited from the seizure by the Nazis of the enamel factory. But as Nazi persecution intensified, he began to actively shield his workers, using his influence and resources to bribe officials and create a safe haven within the factory walls. During the purging of the Kraków Ghetto and increasing deportations to labor and death camps, Schindler fought to transform his factory into a sub-camp of the Plaszów labour camp, providing food, comparatively safe conditions, and shelter to over 1,000 people. In 1944, as the Holocaust reached its deadliest phase, Schindler relocated his factory and staff to the Brünnlitz labour camp in Brněnec, Czechoslovakia, and continued to protect and support his Jewish workers until liberation.

The Jewish Quarter in Kraków is now a thriving area but, as we drove around, we were never far from reminders about what happened here under Nazi occupation. We stopped on Lwowska Street to look at a fragment of the original Kraków Ghetto wall, which stood in the Podgórze district during WWII. The wall was erected to confine the city’s Jewish population between 1941 and 1943, with the shape resembling Jewish matzevahs (gravestones) to add further cruelty and symbolism to the structure. The wall is now a protected monument, on which a commemorative plaque reads (in Hebrew and Polish): “Here they lived, suffered and died at the hands of the German torturers. From here they began their final journey to the death camps.”

Next, we drove to St. Joseph’s Church, an impressive Neo-Gothic building that dominates the Podgórze Market Square.

We continued on to Św. Wawrzyńca (St. Lawrence) Street, past the Corpus Christi Basilica, founded in 1340 by King Casimir III the Great

Our next stop was on Skałeczna Street, at the Basilica of St. Michael the Archangel and St. Stanislaus.

Continuing with the church theme, we headed to Szeroka Street in the Kazimierz area, to see the Old Synagogue, the oldest surviving synagogue in Poland and one of the most significant examples of Jewish fortress architecture in Europe. The synagogue was built in the late 15th century, most likely after 1494 when Jews were resettled to Kazimierz following a fire in Kraków’s Old Town. It was rebuilt and fortified in 1570, gaining its defensive features. For hundreds of years, it was the main synagogue and heart of Jewish life in Kraków, serving as both a house of prayer and the central meeting place of the community. The synagogue was heavily damaged by the Nazis, but was restored in the late 1950s.

The area around the synagogue is now a thriving cultural area, with a very nice atmosphere. However, the history here is always present, with the Holocaust Memorial Monument located prominently in a central garden in the area. This monument honours the 65,000 Jewish men, women, and children from Kraków and its surroundings who were murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

At about 3:30 pm, our tour guide dropped us off in the Kraków Old Town, and we walked up Wawel Hill to the castle complex, considered to be Poland’s most iconic historical site. Dominated by the Wawel Royal Castle and Cathedral, it was the seat of Polish kings, the setting for their coronations and burials, and the location of the nation’s most important events from the early Middle Ages until the royal court moved to Warsaw in the 17th century.

From Wawel Hill, we walked back along Grodzka Street, stopping to admire the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, which dates back to the early 1600s.

Just next door to the Church of Saints Peter and Paul is St. Andrew the Apostle Church, built between 1079 and 1098, and considered to be a Romanesque masterpiece. It is one of the city’s oldest and best-preserved historic buildings. It famously withstood the Mongol invasion of 1241, providing refuge for local residents thanks to its thick stone walls and defensive windows.

Adjoining the church is the Poor Clares Monastery, a convent founded by the Order of Saint Clare, a Catholic order for women following the ideals of St. Clare and St. Francis of Assisi. It has been home to the order in Kraków since the 14th century.

We continued walking down Grodzka Street to the Rynek Główny, Kraków’s main square. This square, one of the largest medieval squares in Europe, is dominated by the Town Hall Tower, a Gothic structure dating back to the 14th century.

Also in the square is St. Mary’s Basilica, one of the city’s most famous landmarks. The basilica is known for its striking brick Gothic architecture and its two towers of different heights. Every hour, a trumpet signal called the Hejnał mariacki is played from the taller tower, commemorating a 13th-century trumpeter.

On the other side of the square is Sukiennice (the Cloth Hall), a Renaissance-era market hall that was historically the centre of Kraków’s international trade, especially in textiles, spices, and other luxury goods.

By now it was about 5:30 pm and, having skipped lunch, we decided that we’d stop for some dinner. We found a lovely restaurant in a backstreet and enjoyed a wonderful meal.

After dinner, we walked back through the square and then down Floriańska Street, which was very lively.

We left the Old Town via St. Florian’s Gate. Built in the 14th century as part of the city’s defensive walls, the gate served as the main entrance to the city. It is the only remaining city gate of Kraków’s original medieval fortifications.

Just through St. Florian’s Gate is the Kraków Barbican, a circular Gothic fortress built in the late 15th century to protect the main entrance to the Old Town. It features massive brick-and-stone walls (around three metres thick), seven turrets, and over 100 defensive loopholes. Originally surrounded by a moat, it was a formidable stronghold against invaders, exemplifying medieval military engineering. Today, it is one of Europe’s best-preserved barbicans.

From the barbican, we walked past Matejko Square, named after the Posih painter, Jan Matejko. The square contains the Grunwald Monument, an imposing equestrian statue of King Władysław II Jagiełło, unveiled in 1910 to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the historic Battle of Grunwald, where Polish and Lithuanian forces defeated the Teutonic Knights.

We got back to the train station a little before 7:30 pm, with plenty of time to spare before our scheduled 7:56 pm departure to return to Warsaw.

We had a very comfortable trip back to Warsaw. We arrived around 10:20 pm, and caught a taxi back to the hotel, where we promptly fell into bed.

Tomorrow, we are flying to Budapest in the afternoon, where we will be catching up again with Peter and Joy, who are flying into Budapest tomorrow from Berlin.